God’s creation is “pied” or multi-colored, tinted, and variegated as Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “Pied Beauty” celebrates:

Glory be to God for dappled things

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim…

Everywhere one looks he sees a universe of mixed, blended hues from the sky above with its patchwork of blue background and white clouds to the rainbow colored trout below in the water. Mother Nature’s four seasons regularly change their clothing and colors to prevent sameness and monotony.

Human beings eat a variety of foods with a wide range of taste to nourish the body with all the different groups of food needed for health. Nature’s beauty and abundance provide the variety essential for man’s state of happiness and health.

Without it even luxuries lose their pleasure as the wealthy prince of Abyssinia in Dr. Johnson’s Rasselas discovers:

“Variety . . . is so necessary to content that even the happy valley disgusted me by the recurrence of its luxuries.”

Likewise, the human mind also needs the contrasts and changes that variety of different disciplines offers to be alive and engaged. Although human beings require order and permanence in their lives which the regularity of home, work, and church provide, they also thrive with doses of newness and variety that make life surprising and stimulating.

The art of living is the ability to relish many of life’s great sources of happiness and to enjoy the abundance of joy that life offers. C. S. Lewis remarked that not to have read the great books of literature is like never having been in love, never having swum in the ocean, and never having tasted wine.

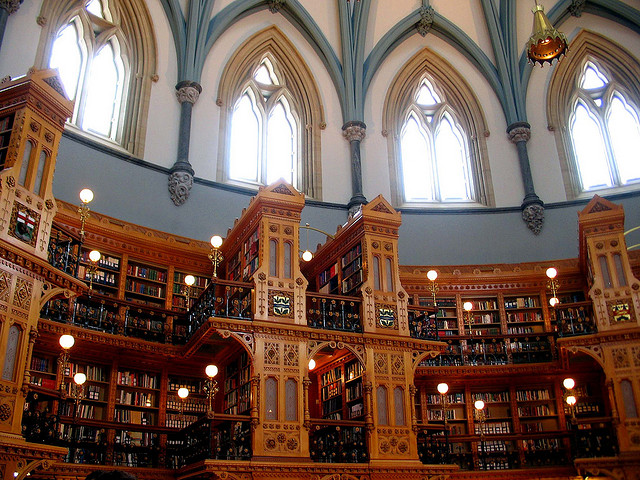

Parliament Library CC Jenn Calder

One should not live without partaking of these gifts intended for the riches of human happiness. These exquisite pleasures are created for the pure delectation of tasting life’s sweetness.

An Ancient Artistry

In Homer’s Odyssey the civilized practice this art during the occasions of their banquets that celebrate weddings and welcome guests. The ritual of hospitality that marks these occasions provides food for the body and nourishment for the soul. Admiring the beauty of the dishware and drinking goblets and savoring the roasted meat and mellow wine, the company then enjoy the pleasure of conversation and storytelling as they ask the traveler to narrate his adventures.

The music of the lyre, the performance of the dancers, and the athletic competition of the games add additional delights to the festivities. The mark of civilized life that distinguishes it from meager survival is the variety and number of pleasures that fill the day, year, and seasons.

The civilized who live well revel in the simple pleasures of good food and sweet wine that gratify the body, the pleasures of the mind that conversation and stories fulfill, the aesthetic pleasures of music, dance, and art that move the soul, and the physical pleasures of competition in sports and athletics that satisfy man’s love of play.

Bored to Death

Melville’s short story “Bartleby,” on the other hand, portrays a scrivener who copies legal documents on Wall Street and lives only to work. He not only works during the day and in the course of the week but also lives in the office, eats in the office, sleeps in the office, and spends Sunday in the office.

He enjoys no family life, experiences no friendships, participates in no leisure activities, and has no favorite hobbies or recreations. Unlike the Greeks depicted by Homer, Bartleby enjoys nothing, not even his work which he performs in a perfunctory way, using merely his hand to copy words but never engaging his whole person to perform a labor of love. His only response to all conversation amounts to “I would prefer not to” when asked to leave the office.

His meager idea of eating amounts to ginger nuts and cheese. Addicted to work and overspecialized in performing the one task of copying, Bartleby not only has never experienced the joy of books, ocean, wine, and love but also seems unaware of any other aspect of life besides the routine of monotonous work.

Without these experiences of reveling in life’s prodigious variety, a person’s sense of beauty diminishes, a person’s capacity for happiness suffers, a person’s mind becomes starved for stimulation, and a person’s humanity becomes deformed into the oddity of an eccentric. As a fellow copyist remarks of Bartleby, “I think he’s a little luny,” and another scrivener comments, “I think I should kick him out of the office.”

God’s pied beauty that fills creation everywhere with the rich contrasts of “All things counter, original, spare, strange” and with a wide range of differences (“With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim”) is as life-giving for the mind and soul as Nature’s harvest of the fields and orchards is food for the body.

The More You Enjoy

The number of pleasures that delight a person indicates the fullness of happiness he enjoys. Not to enjoy Nature, beauty, friendship, books, games, hobbies, music, and even work stunts a person’s humanity and makes him dull company with no common interests to share with others. As St. Thomas Aquinas explains, the more a person enjoys, the more sociable and enjoyable his company because of the mirth he communicates in his relationships.

Those who enjoy little or nothing burden others, “showing no amusement and acting as a wet blanket” and deserving of being called “grumpy and rude.”

Fall CC Toni Verdú Carbó

Hopkins’ love of nature’s variety and appreciation of beauty in its many forms overflows into a rapturous delight in all of creation from the “pied beauty” of the cow, trout, and finch’s wing to the “brute beauty” of the falcon in his majestic flight to the “barbarous beauty” of the fall harvest of the corn to the pristine beauty of the spring (“Nothing is as beautiful as Spring”) to the beauty of the starlit night (“Look at the stars! look, look up at the skies!”).

The experience of beauty moves the soul, breathes life into the spirit, uplifts the heart, and makes one fall in love with life all over again. The fullness of beauty is inexhaustible and without limit.

Delight in Dappling

This great variety brings pleasure after pleasure in all the four seasons and in the multitude of delights especially designed by the God of “dappled things” who paints the vast sky and even the delicate bluebell with azure; who makes an old world ever new and fresh with color and rebirth (“There lives the dearest freshness deep down things”); and who gives hints of the Garden of Eden in the loveliness of spring (“What is all this juice and all this joy?”).

Bartleby, on the other hand, with no favorite pastimes and no sense of life’s enormous bounty of pleasures, brings no spirit into any relationships, remaining as oblivious to the good and beautiful as the ones St. Thomas classifies as “those with no sense of fun, who never say anything humorous, and are cantankerous with those who do.”

Rainbow CC Christos Tsoumplekas

If one never sees the thrush’s eggs below that “look little low heavens,” he will not see the “couple-coloured sky” above. If he does not see the tiny “rose moles all in stipple upon trout that swim,” he will not see splendor of the rainbow that spans the heavens. If one does not wonder at the patchwork nature of the landscape “plotted and pieced,” he will not marvel at the diversity of gifts and talents employed by human nature in all its many occupations, professions, and skills (“And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim”).

If one does not see the beauty of visible things, he will not contemplate the invisible things of God and give glory to the author of all beauty as Hopkins does in the final line of the poem: “Praise him.”

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources