Summary

Leaders in Orwell’s and Huxley’s worlds fear beauty. Dr Mitchell Kalpakgian uses Hopkins’ poetry to reveal why: it has power to lift heart, mind, and soul.In Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World, two of the most prophetic and chilling novels of the twentieth century, the totalitarian regimes that impose an atheistic worldview upon their societies by their policies of propaganda, indoctrination, and social engineering take special pains to banish all experiences of the beautiful from the daily lives of the citizens.

The beauty of craftsmanship, the splendor of art, and the wonder of great literature all pose serious threats to the agenda of Big Brother in 1984 and the Controller in Brave New World. Winston Smith, the main character in Orwell’s novel, laments the dreariness of modern life devoid of every sense of the beautiful:

“It struck him that the truly characteristic thing about modern life was not its cruelty and insecurity, but simply its bareness, its dinginess, its listlessness.”

He observes that no woman in his daily experience gives any hint of attractiveness, elegance, or style. No woman of his political party ever uses cosmetics or perfume, or dresses to be beautiful or exquisitely feminine.

Winston notices the disappearance of antiques and the beauty of workmanship in his daily life. Only in a pawnshop in an obscure part of the city does he uncover the buried masterpieces of an earlier age when he beholds an old-fashioned clock, a curved glass paperweight, and a handcrafted mahogany bed.

When Winston notices the texture and color of the paperweight with coral from the Indian Ocean embedded in the glass, he responds with astonishment, “It is a beautiful thing.”

When Winston realizes that the bells of English churches no longer resound with their peaceful, pealing sound to compose the soul and to bless the day with their joyous music, he recognizes another aspect of the loss of beauty.

No more does he hear the familiar chimes from the past that added joy to the day: “Oranges and lemons, say the bells of St. Clement’s / You owe me three farthings, say the bells of St. Martin’s. . .” Without the beautiful touches that adorn daily life, human existence easily degenerates to the tawdry and pedestrian.

In order for the Thought Police to abolish all Thought Crime originating from the contemplation of the beautiful, all the works of great literature that awaken awe at the miracle of classical art demand censorship or revision:

“The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron—they’ll exist only in Newspeak versions, not merely channeled into something different, but actually changed into something contradictory of what they used to be.”

This is the same view expressed by the Controller in Brave New World who argues, “We haven’t any use for old things here . . . . Particularly when they’re beautiful. Beauty’s attractive, and we don’t want people to be attracted to old things. We want them to like the new ones.”

Dictators must banish all reminders of the old to prevent any comparison between the glories of the past and the banality of the present.

When the beautiful disappears from the landscape, culture, and lives of persons, this loss closes the door to another world, not only the door to the wisdom of the past but also the way to the spiritual realm and the experience of the divine.

Like the True and the Good, the Beautiful identifies one of the attributes of God that philosophers call the Transcendentals. As St. Paul explains, the invisible things of God are known by the visible.

The beauty of creation in all its forms declares the handiwork of God as the masterpiece of an artist. To see the beautiful inspires wonder and awe.

This rapture leads to contemplation and a sense of mystery:

What is the origin of beauty? Who is the author of beauty? Why is the world so luminously filled with resplendent color and abundantly filled with variety? No wonder Gerard Manley Hopkins sees God’s presence in the world everywhere (“Christ plays in ten thousand places”) whenever he encounters the beautiful in its myriad forms:

“Glory be to God for dappled things,” “The world is charged with the grandeur of God,” “Nothing is so beautiful as spring,” “Look at the stars! Look, look up at the skies!” “Summer ends now, barbarous in beauty.”

The beautiful, then, is not merely an aesthetic feeling or experience that pleases the senses.

While it begins with the pleasure of sight—“that which being seen pleases” (id quod visum placet in St. Thomas’ classic definition)—it also stirs the soul, moves the heart, and lifts the mind. It is at the same time a delight of the senses, an excitement of the feelings, and an illumination of truth.

For example, in an encounter with the beautiful in Hopkins’ “Hurrahing in Harvest,” the speaker moves from the physical realm to the heavenly world: “I walk, I lift up, I lift up heart, eyes / Down all that glory in the heavens to glean our Saviour.”

God speaks through beauty just as He speaks through His Word and His Ten Commandments.

Hopkins writes in this poem of “the barbarous beauty” of the fields with corn stalks of all heights, the undulating clouds (“wilder, willful wavier”), the rising and falling shape of a horse’s back (“a stallion stalwart”), and the rolling mountains with irregular contours (“the azurous hung hills are his [Christ’s] world-wielding shoulder”).

To marvel at all this great beauty in the landscape is to wonder also at the copious harvest of Nature’s abundance in the fall— at all the handiwork of the Lord reflected in the rugged, majestic, “barbarous” beauty that inspires man’s soul to rush to God: “The heart rears wings bold and bolder / And half hurls for him, O half hurls earth for him off under his feet.”

In short, the experience of the beautiful awakens, enlivens, and stirs the heart which lifts, rears, and hurls “to glean our Savior.”

Godless secular worldviews and radical ideologies advance their atheism by banning all the images of the beautiful that naturally express the reality of God’s presence in the world.

No one encountering the beautiful can view the world around him as the state of bareness, dinginess, or listlessness that Winston observes as the condition of modern life. Because Winston sees no antiques, hears no bells, sees no great art, reads no classics, and notices no adornment or beautification of the human form, he suffers a dehumanized life.

Big Brother had stifled emotional, spiritual, and intellectual life by the politically correct proliferation and circulation of “newspapers, films, textbooks, telescreen programs, plays, and novels” intended to brainwash, deaden, and numb a person’s normal human sensibility.

“The rubbishy newspapers” offering only sports, crime, and the horoscope fill man’s mind with unimportant information and make him unconscious of the sacred.

While the harvester beholding the cornucopia of the field and the barbarous beauty of the autumn “rears wings bold and bolder / And hurls for him,” Winston reading only the newspapers and viewing the telescreen with their sensationalistic stories and repetitious slogans exists as a creature of the state.

He has no mind in love with truth, no heart filled with passion, and no soul in awe with “barbarous beauty” and “all that glory in the heavens.”

Without the beautiful as an integral part of all human lives, the mind atrophies, the spirit dulls, and the heart becomes hardened. The world shrinks into dinginess.

An Orwellian universe and a politically correct world kill the soul and leave a person powerless to transcend the dreary, drab world imposed on him by ideologues fearful of the meaning of beauty.

Beauty has emotional, intellectual, and spiritual power to make man think of the eternal, the heavenly, and the holy as the ultimate realities and highest objects of thought, not the messages of the media that repeat, “The Party is always right.”

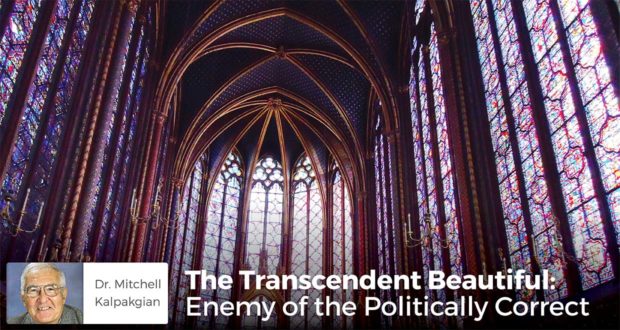

Header photo CC: David Rowlzi – Sainte Chapelle Cathedral – Paris

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources