Throughout the Middle Ages artists and poets allude often to the goddess Fortuna or the Wheel of Fortune—the ever changing nature of human events that affect all human beings.

This idea is familiar in the marriage vow that promises “for better, for worse; in sickness and in health; for richer or poorer.”

All persons are subjected to the ups and downs of fickle Fortune whose whimsical nature is erratic, random change. Everyone’s state of health, happiness, or economic status is subject to unpredictable reversals.

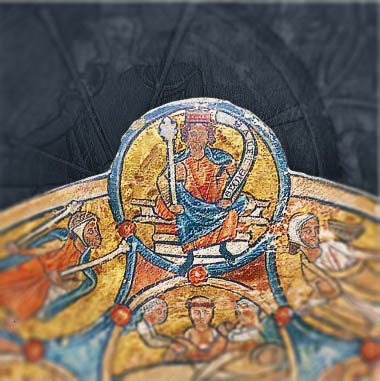

Often Fortune appears all-powerful and all-controlling and man merely the plaything of the Goddess Fortuna.

The 4 Parts of the Wheel

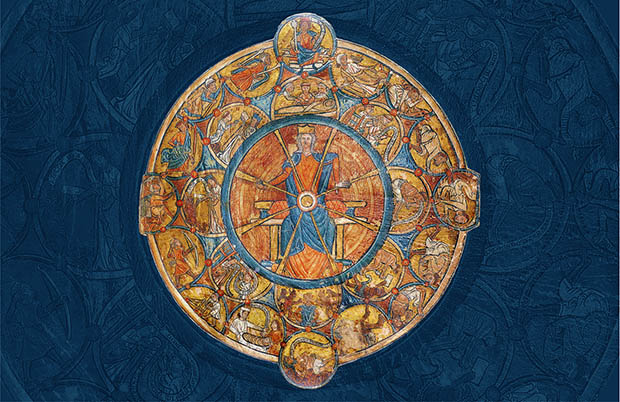

Medieval art portrays the Wheel of Fortune with vivid images that depict the state of man at the various stages of the wheel. As it turns clockwise, a king with the name “Regno” (I rule) stands erect at the 12 o’clock position with a scepter in hand.

In the next picture at the 3 o’clock hour, the same powerful ruler who reigned supreme a moment earlier at the throne of power has slipped and appears in a state of falling. His name changes to “Regnavi” (I have ruled).

In the third image at the 6 o’clock hour, the king lies prostrate at the bottom of the Wheel of Fortune, weak and dethroned. This position represents the classic definition of tragedy, “a sudden fall from high to low.” The new name he assumes at this stage is “Sum sine regno” (I am without rule).

In the final picture at the 9 o’clock hour stands Regnabo (“I will rule”) as the ruler rises from his fall and begins to climb the wheel to resume his former status as all-powerful king and regain the name of “Regno.”

These stages on the Wheel of Fortune depict the universal human condition that all men experience.

1. Ruling with Power & Pride

1. Ruling with Power & Pride

However, at each of the four stations on the wheel, man is subject to a particular temptation that requires a specific virtue to combat it. “I rule,” the person at the top, is most vulnerable to pride. Because he rules with power, he imagines he is omnipotent and invincible. He cannot conceive of losing his reign, suffering defeat, or finding himself at any other position on the wheel except the highest.

He forgets the temporal nature of human happiness and the fact that all human happiness is a mixture of joy and sadness. “Pride goeth before a fall,” as the Book of Proverbs teaches. “I rule” needs the virtue of humility to protect him from fantasies of greatness or assumptions of infallibility. No wise, humble person ever assumes that the pleasure or joy of the moment lasts forever in a fallen world.

No wise person forgets that the word human means dust or dirt just as the word humus refers to soil. Chaucer’s “The Monk’s Tale” cites many examples of the prideful who are humbled by their sudden falls from high to low: Lucifer, Samson, Adam, Nero, Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great.

2. Anger at Injustice

2. Anger at Injustice

The person in the position of “I have ruled” suffers the temptation of wrath, anger at the unexplainable, irrational turn of events that makes him decry life’s cruel injustice. His sense of defeat and frustration make him doubt God’s goodness and wisdom in permitting this inexplicable loss of happiness.

The virtue that opposes wrath is meekness, a resignation to the fact that many events lie outside of man’s control. The meek never seek retaliation or return evil for evil when the Wheel of Fortune topples them from the pinnacle of prosperity. The meek also exercise the virtue of patience that fortifies a person to endure the vicissitudes of life. Tribulations, disappointments, and misfortunes must not rob a person of the will to persevere, endure, and remain constant.

As Roman Stoics like Marcus Aurelius taught, no one can control the changeability of weather, political events, or the conduct of other people, but everyone can exercise self-command and self-control—the virtue of equanimity.

3. Fallen from the Heights

3. Fallen from the Heights

The person who suffers the fate of “I am without rule” remains in a state of stupor at the sudden loss of power, status, or pleasure, shocked at the radical change in his life from the heights of happiness to the depths of misery.

Like Hamlet he laments the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” and struggles with the temptation of despair. He views himself as utterly powerless, a victim of unpredictable forces beyond his control, someone as insignificant as “a feather in the wind” or “a dot made by a fine pencil” to use Montaigne’s phrases when he compares his powerlessness to Fortune’s might. In Hamlet’s mournful words, “To be honest, as this world goes, is to be one man picked out of ten thousand.”

The person lying prostrate at the bottom of the wheel also suffers from the temptation of sloth, a product of the extreme sadness inflicted by the humiliation of defeat. The antidote to these vices is hope, zeal, and fortitude. In a large world full of infinite possibility, it follows that, in the proverbial saying Don Quixote utters to Sancho Panza, “Where there is life there is hope.”

Zeal releases will power and effort to combat the listlessness and world-weariness of sloth, and fortitude demonstrates conviction and passion in the midst of great obstacles, fully aware that the good is difficult and often demands Herculean strength.

These virtues attribute to man the power to act, the ability to change and influence the shape of events rather than merely to react to circumstances outside his control.

4. The Ease of Ambition

4. The Ease of Ambition

“I am about to rule,” the person who eventually recovers from the blows of fickle fortune and attempts to rise again and ascend once more to the top of the wheel, easily submits to the temptation of ambition.

Close to the highest point but still in a lower position, the urge to rise and gain often leads to rash, impulsive deeds, unscrupulous schemes that dare to “rape Fortune” by brute force in the way Macbeth seizes the kingship from King Duncan by treacherous murder.

The person close to power or second in authority is tempted to take matters into his own hands and not let events naturally shape the future. When Macbeth heard the witches prophesy “King thou shalt be,” he did not wait to see what these words foretold but asserted bold ruthlessness in his ambition for kingship.

Instead of rising to the heights of Fortune in a natural, moral sequence of events, those “about to rule” plunge with reckless abandon to gain their wishes without counting the cost of tragedy they will suffer. Like Machiavelli, they think the end justifies the means or convince themselves it is their fate.

The virtue that combats the temptation of ambition is prudence, foresight on behalf of others and not for the sake of self-interest. Prudence always seeks to do what is just and right by honorable means, not by devious stratagems. Prudence always knows that one can never do evil to accomplish good. Macbeth can inherit or succeed to the throne, but he cannot usurp the king’s position by foul play.

Temperance also cures covetousness; it is the virtue of moderation the Greeks called “the golden mean”—neither too much nor too little. Macbeth already enjoys the titles of Thane of Glamis and Thane of Cawdor, but his insatiable desire for greater power, his “vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself,” impels him to seize the prize by listening to the equivocations of the witches who promise all but deliver nothing, making Macbeth reflect, “Naught’s had, all’s spent.”

Round and Round…

Human experience leads a person up and down the Wheel of Fortune many times in the course of a lifetime. Each stage beckons man with its various temptations from pride to wrath to despair to ambition, and each stage compels man to resist the temptation with an opposing virtue from humility to meekness to fortitude to temperance.

No matter how powerful, erratic, or strange the ups and downs of Fortune’s wheel, Fortune is not the goddess who rules the world or taunts man with her tricks. Whatever Fortune brings, man’s virtue can overcome.

Although no man can control fickle Fortune, every man can control his desires, passions, and appetites. The one who resists these temptations that Fortune constantly brings is godlike, steadfast, and indomitable.

He, not the goddess of Fortune, is the powerful ruler.

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources