In The Way of a Storyteller Ruth Sawyer tells an anecdote about a gifted furniture maker renowned for his craftsmanship whose work was in great demand by the prominent and wealthy. Regardless of how busy or demanding his schedule, he always paused from his labors every year to perform in an amateur opera with the other artisans of his city.

One of his patrons who found this practice impractical complained of the waste of time spent in rehearsing and producing an opera, valuable time that should have been devoted to the business of cabinet making and the pleasing of customers. In his self-defense the carpenter justified the love of opera and joy of singing by insisting that his recreation was not a question of irresponsibility or negligence toward his profession. He explained to his patroness, “All the goodness, the lift of the heart that we got out of playing in those operas, we would put back into our work—in the draperies and tapestries we hung, in the cabinets we made.” In other words, the quality of a man’s work in his profession depends on the love and joy he brings to his art. The labor of human hands does not merely depend on the expertise of the worker’s skill but also on the state of mind and heart that a laborer brings to his profession.

Without “the lift of the heart” inspired by play, fun, and recreation, the creative energy of the human spirit atrophies and the quality of the work suffers. The carpenter reassured his customer, “Nothing was lost” in the interlude of the opera that interrupted the routine of his work. “That is how it should be when you have experienced something great and beautiful. Gnadige Frau, something of those operas will go into your sofa.”

This episode illuminates an important truth about the art of living. Not everything a person does needs to be justified for its practical benefits or utilitarian reasons. While some things are a means to an end and have a “servile” function, other things are to be pursued as ends in themselves.

While driving a car or earning money is a means to an end with the useful object of reaching a destination or purchasing the necessities of life, they are not “liberal” (free) activities that are loved for their own sake as ends in themselves. On the other hand, the enjoyment of an opera, the pure delight in a favorite recreation or sport like fishing, or the innocent mirth of the pleasure of friendship need no justification in terms of profits, benefits, or results. Children play for only one reason—for the sheer fun of the activity.

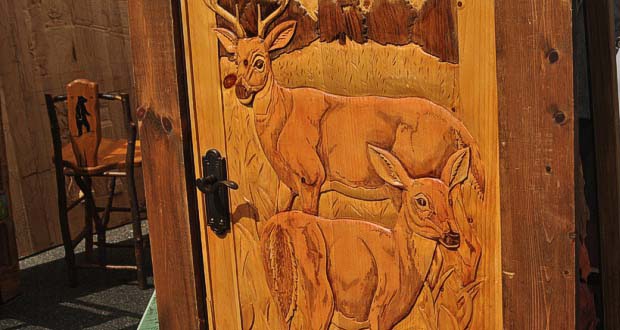

These “liberal” pursuits loved for their own sake and not for their useful gains have the greatest benefits even though they are often misjudged as idle, frivolous activity. The carpenter insisted that “nothing was lost” during this pause from work because it rejuvenated his spirit and filled his heart with the joy of music and the love of life that overflow in the beauty and perfection of his craftsmanship. The music of the opera goes into the art of woodworking because of “the lift of the heart” that fills the soul of the artisan who works not merely for pay but as a labor of love. Operas are not wastes of time or distractions from the serious business of work, as the patroness imagined, but vital for an exuberant human life.

The pursuits of fun and play are not useless because they rob a person of time and money but simply good in and of themselves. As Blessed Cardinal Newman explains, “Good is not only good but reproductive of good; this is one of its attributes; nothing is excellent, beautiful, perfect, desirable for its own sake, but it overflows, and spreads the likeness of itself all around it.”

Singing in operas makes gifted carpenters.

What have you done recently that had no practical benefits or utilitarian reasons other than to lift up your heart? What “liberal” pursuit has rejuvenated your spirit and increased your love of life?

Header Image CC greymaster

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources