When I was in first grade, I loved to go down the hall of my elementary school and visit my older sister’s sixth-grade teacher.

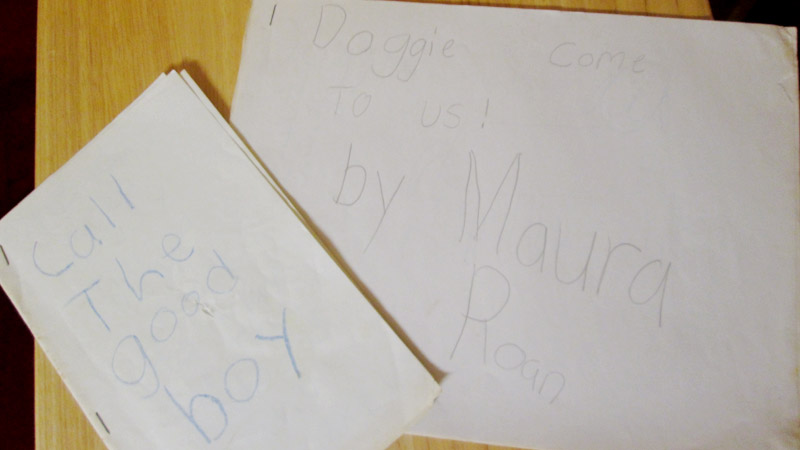

I would staple together a few sheets of white paper, scrawl a story in two or three giant words per page, and carry the “book” to Mrs. Cutler, who would make a big fuss over it and beg me to bring her more.

These were not exceptional stories. I still have a few that prove their mediocrity.

But when Mrs. Cutler praised my efforts, she gave me a gift I still treasure: she inspired me to write.

Later, when I became a teacher myself—first in the classroom and then in the home—I wanted to give that same gift to my students.

The Writing Workshop in the Classroom

I’ve seen many writing programs in my years as an educator, and the approach that most closely resembles my childhood experience is the one advocated by author/educator Lucy Calkins in her book, The Art of Teaching Writing (Heinemann Educational Books, Inc. 1986).

Calkins describes the “writing workshop,” a method of classroom writing instruction based on the writing process approach. In the writing workshop, children choose their own topics, write stories, share their writing with a trusted audience, receive feedback and encouragement, and gain confidence as they begin to see themselves as authors.

The philosophy behind the workshop is phenomenal, and I recommend the book for anyone interested in helping children learn to write. Although it is a classroom-based approach, homeschooling parents and other educators will find universal pointers for teaching writing, presented in Calkins’ anecdotal, enjoyable style.

The format of the workshop is intentionally kept simple: the permanent pillars of the mini-lesson, writing, conferencing, and sharing form the supporting structure that gives children the freedom to write without always wondering what will come next. As the predictability of the liturgy enables us to open our minds to prayer, so the predictability of the workshop enables children to open their minds to writing.

In this method, children write about what matters to them, and find their voices as authors when they read their writing aloud to an audience. Younger children learn to put their ideas on a page and communicate themselves to others through writing.

Older children learn to use the steps of rehearsal (also known as prewriting and brainstorming), drafting, revision, editing, and publishing, to give permanent life to their unique ideas and experiences. Everyone learns to encourage other writers by listening and responding to their classmates’ work.

The Writing Workshop in the Home

It would be difficult to enact the writing workshop according to Calkins’ specifications in a homeschooling environment, mostly because the one she advocates is held ideally for an hour every school day, with a class of peers.

Although a family with many children might pull it off, most homeschoolers would have difficulty meeting daily with enough other families to create the kind of environment the writing workshop calls for. Calkins states clearly that she believes students should write daily in order to keep their momentum going.

However, a few years ago I decided I wanted to figure out a way to adapt the writing workshop to fit a homeschool model. I had used the writing workshop approach when I was a classroom teacher, and I strongly believed in its merits. I wanted my own children to experience it. Though I knew I couldn’t duplicate Calkins’ classroom-based method, I believed that having some form of writing workshop would be better than none at all.

In order to create a practical way for us to host a writing workshop in our home, I devised a compromise. Our homeschool method centers around one weekly group workshop, yet offers opportunities for children to continue writing at home on other days.

Elements of the Workshop

Our homeschool writing workshop contains five main elements: prayer, read-aloud, mini-lesson, writing, and sharing.

1. Gathering in Prayer

As an author, I know that praying about each piece is the most important aspect of my writing. Without God’s help, I cannot write well. I want the children to remember that writing is a gift from God, and when we ask the Holy Spirit to inspire our writing, we use our gifts for His glory.

So, to begin our workshop, we gather on the floor in the family room and say a brief prayer, concluding with, “St. Francis de Sales, patron saint of writers, pray for us!”

2. Reading Aloud

“The best writing teachers I know…weave literature into everything that happens in the writing workshop,” says Calkins. Good writing inspires good writing. That’s why we read something inspiring before we write.

The children sit on the floor while I read aloud a favorite (well-written) picture book or short story. Often, I briefly point out one thing about the author’s style (“I really like how the author made the wind talk like a human person. This technique has a name: it is called ‘personification.’”), but I’m careful not to overdo it or pull apart the book too much.

Our goal is simply to enjoy the pleasure of reading the author’s writing together.

3. A Mini-lesson About Writing

I present a mini-lesson about an aspect of writing. This lesson is short (5-10 minutes), direct, and specific.

For the first few meetings, this mini-lesson will cover the logistical aspects of the workshop and starting points for writing:

What should we write about? [Something important to you! Something you know about! Something you care about!]

How will we do it? [Just write! Write a draft, in whatever way you’re comfortable. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or handwriting at first. Just get your thoughts down on the paper. Then, you can go back later to make content changes (revise), fix spelling and grammar (edit), and put it in your best handwriting (publish).]

Later, as the children’s writing develops, mini-lesson topics often spring from things I notice in their writing. If I want to encourage them to use dialogue, for example, or to employ stronger verbs, I will teach them about it during the mini-lesson.

4. Down to Writing

After the mini-lesson, everyone writes. At a minimum, children should have 30 minutes of writing time. When possible (i.e. when babies and toddlers let me), I write during this time, too, to show the children that I continue to work on my own writing, just as they do theirs.

In my experience, switching environments gives the writing time a breath of fresh air, so we go to a new room of the house to write.

Most children write better at a desk or table, so we set up our writing station at the dining room table, but if any child feels more comfortable writing elsewhere, they are permitted to go where they please (including the floor) as long as they can stay focused. Writers need to be comfortable where they’re writing.

Before the class arrives, I set up the writing room with all necessary materials so that no class time is wasted.

Younger children, who cannot be expected to keep track of an ongoing story or to use the full writing process yet, will likely write a new story each week.

Their stories might only be a few words accompanied by pictures. They might invent spelling or leave out words. When they share later, the few words on the page might become a longer verbal story. All of these are steps in the process of learning to write, just as babbling, approximating words, and using broken sentences are steps in the process of learning to talk.

The more these children attempt to write, the better they’ll write. The most important thing we can do is to be enthralled with what they produce!

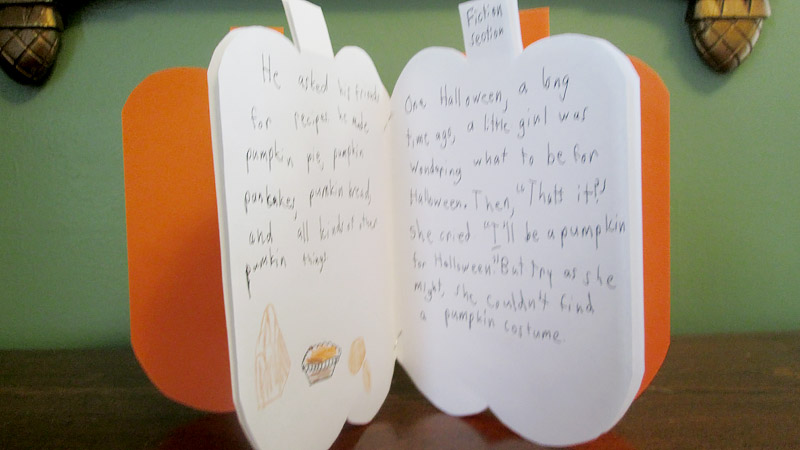

Older children can learn how to take a draft through the steps of the writing process until they have a published final piece. However, not every draft needs to be published. The children themselves must be the ones to decide whether they wish to publish a piece—whether they like the draft enough to bring it to publication, or would rather start a new piece.

During writing time, the room should be quiet so that writers can focus without distraction. Writers must be able to concentrate without interruption, so this is not a time for group instruction.

It is, however, a time when conferences can be held. A conference happens when a writer wishes to read his/her piece to a classmate, or to the teacher, and receive feedback on the piece.

This can be done quietly, in the hallway or a nearby room, to minimize distractions. This one-on-one time between teacher and student is an excellent opportunity to coach the child with personalized instruction, and especially—this is essential to the writing workshop philosophy—to celebrate the child’s efforts and to encourage and affirm the child’s writing.

(For a child with several weak areas, it is best to focus on addressing one or two points at a time, rather than overload the child with corrections.)

5. Sharing Sessions

In a classroom setting, several children will share their work aloud at the end of each session. In a home setting, I offer all children the chance to share what they have written each week. We have two sharing sessions: one at the beginning of the workshop, and the second at the end.

The first sharing session (after the opening prayer) is an opportunity for the children to share the work they have written during the week. I end each class by giving the children “bring-back books”—blank books they can take home, write a story in during the week, and bring back to share.

Some children fill these; others write in notebooks or elsewhere, but every child who would like to share something he or she has written during the week may share it during this time.

I’ve had children bring in several stories each week, or even a chapter or two per week of one long book project that lasts all semester. (When possible, I share something I’ve written, also.)

The second sharing session (at the end) is for children to share what they’ve written during class time. A piece does not need to be finished in order for a student to share; in fact, it helps if it’s not done, because the student can get ideas for how to make the piece better through sharing it.

I’ve had students work on and share the same piece week after week, and everyone sees how the piece changes from draft to final product as the student, through reading it aloud and receiving feedback over and over again, finds many ways to revise and edit it to make it stronger.

I’ve also had students who finish a new draft each week, but after reading it aloud, go back to add words or change phrases that they didn’t notice before. The simple act of reading aloud one’s own writing helps an author to catch errors and notice inconsistencies about his own piece.

Reading aloud also helps the student to notice the feel and flow of his work, reminds him that he’s writing for an audience, and gives him a chance to receive important feedback from that audience.

The writer sits in an “author’s chair” (any chair will do—just call it the “author’s chair” and it takes on a new life!) in front of the group. The rest of the students sit on the floor in front of the author.

It’s essential to form trust among the students in order for authors to feel comfortable and confident sharing their writing, so we set high expectations for the students’ behavior during sharing time.

Before we begin sharing, I remind them that it is time for every student in the audience to be listening (not fiddling with his or her own folder, whispering to a neighbor, or finishing a piece) with eyes on the speaker. When the author has finished reading a piece aloud, the students can raise their hands with questions or comments for the author. The speaker then calls on each person one at a time.

Through experience, I have found it wise to remind the students at the start of each sharing session to keep their comments positive. No one is ever to say something that might make an author feel embarrassed or uncomfortable about his work. It is NOT a time to scout for errors in others’ work. Rather, this time is meant to build the writer’s confidence with praise and encouragement—to celebrate the work and ideas that this wonderful young author was kind enough to share with us.

I always raise my hand, too, so that I can model the specific feedback that is most helpful to a writer.

Getting Started

Each time we host a writing workshop, we learn more about what works best in the home. In planning a writing workshop, these are some of the things I take into consideration.

Class size: We aim for a group of 6-8 children. (Someone with a larger home might be able to accommodate more students.) Having three or more families involved ensures more steady attendance, so that if one family is unable to come, others will still make it.

Age range: One of the wonderful things about this model is that it can accommodate a wide range of ages. Younger writers can learn from older writers, and vice versa. We’ve had first and fifth graders in the same class, with great results. Yet it also works well with a group of students who are in the same grade.

Meeting times: We meet 1 ½ to 2 hours, once a week. (Larger groups will need the longer time.)

Preparing for the Workshop

Here are the things I do in advance.

Before the first meeting:

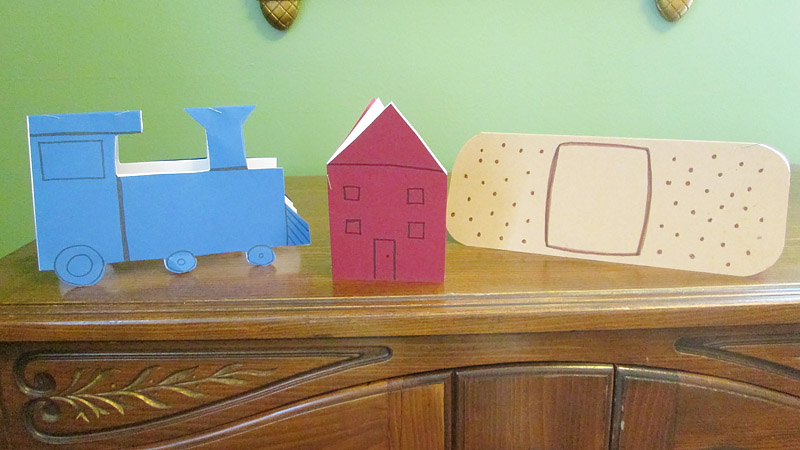

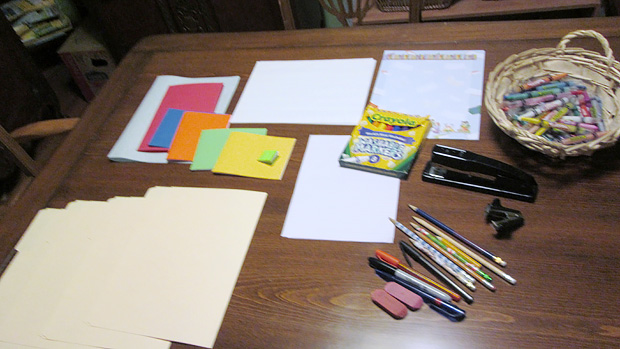

Purchase or have on hand: A large manila file folder for each student (to store writing); assorted writing utensils (pens, pencils, pencil sharpener, markers, crayons, erasers); a stapler; scissors; white-out; and assorted paper (lined, unlined, colored, bordered, etc.), including colored card stock.

Reread (or review) The Art of Teaching Writing by Lucy Calkins.

Before each class:

Staple together “books” for the children to write in if they choose. These books can be very simple or, if I’m feeling creative and have time, more complex. I found that younger children love to have “shape books” (books in the shape of a bear, star, heart, snowman, pencil, cloud, tree, and so on), which usually trigger inspiration for their stories.

Other children might like books of a unique size, (tiny “mouse books” or big “giant books”), a particular color of cover, fewer pages, or more pages, so I try to make a wide variety. (Some students prefer just to write on regular paper, so I have that available, too.)

Place the children’s folders on the writing table with names displayed so the children can find their own folders quickly.

Set out writing utensils, assorted writing paper, and pre-made books.

Choose a worthy read-aloud book. Sometimes I put a post-it note on a place I want to remember to talk about (for example, a good example of metaphor, unique style, or some other writing technique or skill).

Plan a mini-lesson based on what I think the class needs to learn.

Set aside an assortment of books to bring out at the end of class, for children to choose as “bring-back books.”

Class Time

When the children arrive for class, they know what to expect, because we have a basic format that does not change. For example, let’s say that the class meets from 2-3:30. An overview of our time together would look like this:

2:00—Opening Prayer

2:05—Sharing of bring-back books

2:20—Read-aloud

2:30—Mini-lesson

2:35—Writing

3:10—Transition (Move to another room for sharing, and take a stretch break.)

3:15—Sharing of new writing

3:30—Children return writing folders to me and choose a bring-back book to take home.

That’s the homeschool writing workshop in brief. Again, Calkins’ book contains a more in-depth analysis of how best to facilitate a writing workshop, and it wouldn’t be possible for me to cover every detail in this article, but I wanted to share this simple model because I believe that, even at this basic level, it has the potential to inspire young writers and to help them grow in the craft of writing.

I don’t put it forth as the “only way” to teach writing, but as one avenue, out of many worthy ones, to help homeschooled children to not only learn to write but love to write.

A Little Afterword

I wrote this article during the summer—and it had been months since our last writing workshop.

In the midst of it, without knowing that I was writing about this topic, my nine-year-old son went through his school basket and pulled out a five-chapter book called “The Snowman Underground,” which he wrote during the past school year.

He proudly brought it to my husband and asked what he would need to do in order to get it put on the shelf at the public library.

This is the gift—the gift Mrs. Cutler gave to me—the gift the writing workshop gave to my son. His confidence, enthusiasm, pride in his work, and reaching for high goals: this is why we do it. And this is why I’m writing about it: so that others might receive the gift, too.

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources